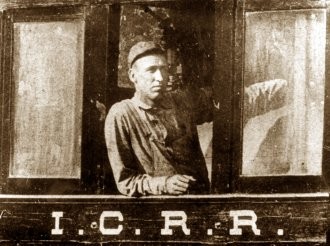

Casey Jones was not a fictional character. He was a well known train engineer before his death, but his real lasting fame came from the fact that he was at the controls of an Illinois Central Rail Road engine that famously crashed at Vaughn, Mississippi in April 1909. That event and his "everyman" personna combined to make him the subject of a number of songs that told the story of the wreck.

John Luther Jones was born in 1863 in Missouri. He was raised in Cayce, Kentucky which provided him with his nickname “Casey.” Jones began his railroad career at the age of 15 as a telegraph operator, later becoming a brakeman, then a fireman. The ‘yellow-fever’ outbreak of the late 1880’s opened up the door for many firemen to promote to engineer and Casey was one of them. He was by more than one account an ambitious engineer, eager to move up the ranks and serve on the better-paying, more prestigious passenger trains which he eventually did. In the view of some engineers he was overzealous and fearless; doing whatever it took to maintain the schedule and arrive on time “as advertised.” In that respect he might have been a company man, however, over his career Jones was issued 9 citations for rules infractions with a total of 145 days suspended. But those penalties would be less severe than the penalties for running behind schedule. It seems more likely that Casey’s motivation for speed was more about his personal finances, less about commercial promises.

On his final run on April 29th 1900 Casey was driving Engine No. 382, pulling freight not passengers, substituting for an engineer who was ill. His train was over an hour and thirty-five minutes late for its departure from Memphis, bound for New Orleans. But as one historian wrote: “Casey had a good engine, a good fireman, and a light load….the perfect setting for a record run,” and before No. 382 reached Vaughn, Mississippi it was only five minutes behind schedule. It would have been a record run.

But there was a problem just ahead: At the switching station at Vaughn two other trains pulled onto the passing track to allow No. 382 to pass but a broken air line on one train prevented it from moving completely off the main track. Four cars remained on the line.

According to the official accident report a flagman was sent to warn Jones’ oncoming train but for unknown reasons Jones didn’t see the flagman or the signal torpedoes that he set off. Jones’ fireman Sim Webb** survived the accident by jumping off the engine at the last minute. Webb testified that he saw the flagman and heard torpedoes at the same time he saw the stationary caboose they were rapidly approaching. That would suggest that they had been “short-flagged” and simply didn’t have enough time or track to stop. The railroad's formal investigation however concluded that "Engineer Jones was solely responsible for the accident as consequence of not having properly responded to flag signals."

Casey was killed; the only fatality of the accident. Why he stayed on the engine is somewhat of a mystery since he had already accomplished everything he could possibly do to slow the train down before impact. For those who see him as a hero he had remained at the helm because he wanted to be there on the chance that there was something else for him to do to avert the crash. That he was the only casualty is testament to his ability to slow the speeding train down enough to lessen the impact. Jones was removed from the wreckage alive, his neck or head pierced by a piece of metal or wood. He died a short time later stretched out on a baggage wagon. His body was taken to Canton in a baggage car and then home to Jackson, Tennessee for burial.

Shortly after the accident “The Ballad of Casey Jones” was written by

Wallace Saunders, an African-American engine cleaner for the Illinois Central

Line who knew Jones personally. It was

sung to the tune “Jimmy Jones” which was a popular song at that time. Carl

Sandburg has called this the greatest American ballad. Engineer William Leighton heard Saunder’s

song and passed it on to his brothers Frank and Bert who were vaudeville performers.

They added a chorus and began to perform it as part of their act. When the

ballad was finally published in 1909 the words were credited to T. Lawrence

Seibert with the music credited to Eddie Newton. These two guys were also vaudevillians and they had

produced a comic version of Casey’s story that his widow took exception to

because of how she was portrayed - as running off with another engineer - when

in reality she remained widowed and dressed in black until the day that she

died in 1958.

The next major change to Casey's story came from Joe Hill. John McCutcheon refers to Joe Hill as “a utilitarian songwriter.” Hill was a labor activist and union martyr who played the piano, wrote lyrics and applied them to popular melodies to inspire the labor movement at rallies, meetings, and on picket lines. His very first composition emerged out of a labor strike that took place in San Pedro, California in 1913 that halted Southern Pacific railroad activity on much of the west coast.

For his first effort at composing Hill borrowed a well-known song and changed the lyrics. “Casey Jones,” a song about a hero engineer became “Casey Jones Union Scab” about a shill of the railroad who didn’t care about workers rights or safety. Hill’s song is a piece of lyrical brilliance that illustrates all the problems confronting railroad workers at a time when the railroads were the most powerful industry in the nation. Unfortunately associating Casey the fictional protagonist with the corporate giants does a true disservice to Casey the real man. The real Casey Jones was a member of two Engineer unions which suggests that he strongly supported the principles of the labor movement. It also shows Casey's concern for his family's security, for one of the benefits of union membership was life insurance protection. Widow Jones collected from both groups when he died.

In the years since Joe Hill first used Casey for his own purposes the legend and imagery of Casey and his train have proved useful to many other songwriters searching for the perfect metaphor, a compelling character, or just a good story.

On American Pastimes this month lots of "Casey Jones" in a

variety of musical genres. This week versions rooted in the blues tradition: Mississippi John Hurt, Memphis Jug Band, The Balfa Brothers, Chris Smither, David Bromberg Band, Someday Baby, and the North Missisippi All-Stars. But not just the blues: Keller Williams' Grateful Grass, Rod Morris, and John McCutcheon.

** Here's a link to a recording of Sim Webb's first hand account of the accident: http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/Data/Sites/1/mp3/casey_jones%20Simeon%20Webb.mp3